About Green Technology

Addressing the wide-ranging environmental impact of global population growth and industry has become critical to the survival and prosperity of human civilization. Green Technology (also known as "green tech" clean technology, or "clean tech") refers to the development of processes, practices, and applications that improve upon or replace existing technologies that allow us to meet our needs while substantially decreasing our impact on the planet. Focusing on the goals of green technology is becoming increasingly important to an diverse range of industries that includes energy, agriculture, manufacturing, and more.

American Elements is committed to meeting the material supply needs of researchers, industries, and innovators working towards a greener future. We also provide support to research programs such as the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability (IoES) in Los Angeles, CA and funded its Center for Diverse Leadership in Science, the first university center in the world focused on diversity in the field of green technologies.

Climate Change

Currently, the vast majority of the world’s energy needs are met by burning hydrocarbon-based fossil fuels. In addition to requiring non-renewable natural resources that will eventually be depleted, this method of energy production produces greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change, releases toxic gases that comprise the smog that plagues modern cities, and requires expensive and often highly-polluting methods of fuel extraction, refining, and transport. Some of these problems have grown more pressing as fossil fuels have become more scarce, requiring drilling in more remote locations, use of less-ideal raw materials such as tar sands that require more intensive processing, and increasingly complex extraction techniques such as fracking.

Currently, the vast majority of the world’s energy needs are met by burning hydrocarbon-based fossil fuels. In addition to requiring non-renewable natural resources that will eventually be depleted, this method of energy production produces greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change, releases toxic gases that comprise the smog that plagues modern cities, and requires expensive and often highly-polluting methods of fuel extraction, refining, and transport. Some of these problems have grown more pressing as fossil fuels have become more scarce, requiring drilling in more remote locations, use of less-ideal raw materials such as tar sands that require more intensive processing, and increasingly complex extraction techniques such as fracking.

Today there are essentially two approaches to global warming. The first is best known from the work of former Vice President and Nobel Peace Prize Winner Al Gore, as presented in his film "An Inconvenient Truth," holds that global warming should be addressed at its root cause by all of humanity working in consort through technological/industrial innovation and international governmental policy to reduce the quantity of air pollution and CO2 emissions being generated. The second approach is best expressed in the work of the environmentalist Bjorn Lomborg as presented in his writings and books, such as "Cool It" which holds that a "rational as opposed to fashionable" approach to global warming is to recognize that the least expensive method of dealing with its effects is to treat them as they occur sometimes at the very local level. This is based on the premise that when the actual effects are examined in a sober and scientific way, policymakers will discover addressing them piecemeal is significantly less costly in capital than the effort that would be necessary to reduce green house gas emissions to a point where the Earth's temperature actually began to fall again.

Today there are essentially two approaches to global warming. The first is best known from the work of former Vice President and Nobel Peace Prize Winner Al Gore, as presented in his film "An Inconvenient Truth," holds that global warming should be addressed at its root cause by all of humanity working in consort through technological/industrial innovation and international governmental policy to reduce the quantity of air pollution and CO2 emissions being generated. The second approach is best expressed in the work of the environmentalist Bjorn Lomborg as presented in his writings and books, such as "Cool It" which holds that a "rational as opposed to fashionable" approach to global warming is to recognize that the least expensive method of dealing with its effects is to treat them as they occur sometimes at the very local level. This is based on the premise that when the actual effects are examined in a sober and scientific way, policymakers will discover addressing them piecemeal is significantly less costly in capital than the effort that would be necessary to reduce green house gas emissions to a point where the Earth's temperature actually began to fall again.

Alternative Energy

Goal: Meeting the world’s increasing energy needs with cleaner, more sustainable energy sources and harvesting technologies.

In the long term, the solution to the many problems with fossil fuels is to transition to using solely renewable energy sources including solar, wind, geothermal, hydropower, biofuels, and waste-to-energy technologies. Maximizing the potential of these power sources will require innovation in areas such as photovoltaic materials to lower the cost and increase the efficiency of solar power, gas separation materials for efficient use of gaseous fuels, and improved heat-resistant materials for use in solar power plants. The use of cleaner power sources to power automobiles will require improved battery technology for electric vehicles and better fuel cell technology for fuel cell-powered vehicles.

In the short to medium term, however, fossil fuels will remain a significant source of energy, and therefore every effort should be made to make the use of these fuels less damaging to the environment. Efforts aimed at achieving this include the use of “clean coal” technologies to reduce pollution from power plants, as well as technologies such as catalytic converters that reduce emissions from automobiles.

Solar Energy

Another example of a technology intended to reduce both air pollution and CO2 emissions is the use of photovoltaic cells to generate electricity (actually electrons) from photons emitted by the sun. Given the enormous amount of capital today being invested in solar energy technologies globally from Silicon Valley to the Nation of Singapore, solar energy will unquestionably play a major role in reducing green house gas emissions by supplanting hydrocarbons such as oil, coal and gas as our energy source for many applications. From its start solar energy has been essentially a field of materials science. In the 1970s the first silicon-based photovoltaic (PV) cells were produced. These basic cells were created by doping silicon to form two oppositely charged layers.

Another example of a technology intended to reduce both air pollution and CO2 emissions is the use of photovoltaic cells to generate electricity (actually electrons) from photons emitted by the sun. Given the enormous amount of capital today being invested in solar energy technologies globally from Silicon Valley to the Nation of Singapore, solar energy will unquestionably play a major role in reducing green house gas emissions by supplanting hydrocarbons such as oil, coal and gas as our energy source for many applications. From its start solar energy has been essentially a field of materials science. In the 1970s the first silicon-based photovoltaic (PV) cells were produced. These basic cells were created by doping silicon to form two oppositely charged layers.

The efficiency of standard silicon-based photovoltaic cells (composed of crystalline silicon, or c-Si) suffers due to their ability to absorb energy only from a relatively narrow range of the sun's emission, namely visible light in the red to violet spectrum, making them only 32% efficient in terms of total energy conversion. Second-generation solar cells known as thin-film cells combine thin films of various semiconductor materials deposited onto substrates to yield more efficient, thinner, and flexible cells. The three major materilals used in commercial thin film PV cells are amorphous silicon (a-Si), copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) , and cadmium telluride.

Development of third-generation solar cells has focused on researching alternative PV materials and architectures that are more efficient, safer, and cheaper to produce. In particular, much attention has been devoted to perovskite solar cells (PSCs) based on hybrid perovskite-structured crystals such as methylammonium lead iodide and other compound halides. These materials not only absorb light well, but are composed of commonly available industrial chemicals and can be produced at lower temperatures than pure silicon wafers, making them far more cost-effective. Gallium arsenide is another material shown to vastly improve solar cell efficiency; due to their high cost, however, GaAs solar panels are primarily used on spacecraft, where performance requirements outweigh the cost of production.

A number of nanomaterial-based solar technologies are also under investigation. Quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs) utilize quantum dots, sermiconductor nanoparticles that have "tunable" bandgaps informed by particle size. These semiconductor materials include cadmium sulfide, cadmium selenide, lead sulfide, and others. Upconverting phosphor nanoparticles (UCNPs) doped with rare-earth elements have the ability to convert infrared (IR) radiation into visible light. Some perovskite cells use carbon-based fullerene derivatives, some of the best n-type organic semiconductors, to improve efficiency and stability.

Other emerging technologies to boost efficiency include transparent bifacial (double-sided) cells, tandem cells, which layer perovskite films over silicon or another material to combine their individual absorption abilities, and solar thermophotovoltaic devices (STPVs), which use optical nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes to absorb the full energy of sunlight, convert it to heat, then deliver it in the form of visible light to the semiconductor OV materials.

Fuel Cells

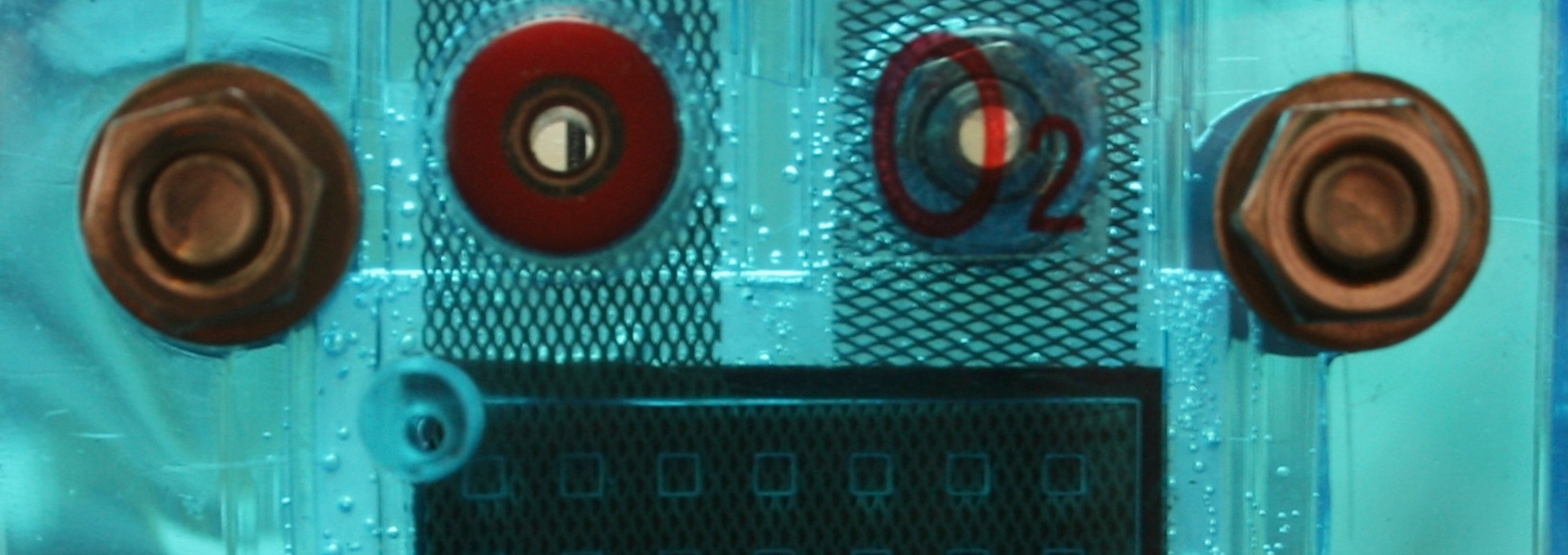

An example of materials science playing a part in eliminating production of greenhouse gases is in the use of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs).

Technologically, SOFCs are all materials science. There are no moving parts in the conversion of hydrogen to electricity. They are comprised of three layers: an electrically conductive cathode made of one of several crystalline perovskite materials such as Lanthanum Strontium Manganite (LSM), Lanthanum Strontium Ferrite (LSF), Lanthanum Strontium Cobaltite Ferrite (LSCF), Lanthanum Strontium Chromite (LSC), and Lanthanum Strontium Gallate Magnesite (LSGM); an ionically conductive electrolyte, such as Yttria Stabilized Zirconia or YSZ (Zirconium Oxide stabilized with Yttrium Oxide), Gadolinia doped Ceria or GDC (Cerium Oxide stabilized with Gadolinium Oxide, Yttria doped Ceria or YDC (Cerium Oxide stabilized with Yttrium Oxide), and Scandia Stabilized Zirconia or SCZ (Scandium Oxide stabilized with Zirconium Oxide; and an electrically conductive anode, which usually is Nickel Cermet compositions of nickel oxide and yttria stabilized zirconia. As hydrogen is pumped under pressure through the electrically conductive anode layer and oxygen is made available through the electrically conductive cathode layer, a circuit is completed through the ionically conductive electrolyte completing the circuit. As long as hydrogen is pumped into the system, electricity will be generated.

An example of materials science playing a part in eliminating production of greenhouse gases is in the use of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs).

Technologically, SOFCs are all materials science. There are no moving parts in the conversion of hydrogen to electricity. They are comprised of three layers: an electrically conductive cathode made of one of several crystalline perovskite materials such as Lanthanum Strontium Manganite (LSM), Lanthanum Strontium Ferrite (LSF), Lanthanum Strontium Cobaltite Ferrite (LSCF), Lanthanum Strontium Chromite (LSC), and Lanthanum Strontium Gallate Magnesite (LSGM); an ionically conductive electrolyte, such as Yttria Stabilized Zirconia or YSZ (Zirconium Oxide stabilized with Yttrium Oxide), Gadolinia doped Ceria or GDC (Cerium Oxide stabilized with Gadolinium Oxide, Yttria doped Ceria or YDC (Cerium Oxide stabilized with Yttrium Oxide), and Scandia Stabilized Zirconia or SCZ (Scandium Oxide stabilized with Zirconium Oxide; and an electrically conductive anode, which usually is Nickel Cermet compositions of nickel oxide and yttria stabilized zirconia. As hydrogen is pumped under pressure through the electrically conductive anode layer and oxygen is made available through the electrically conductive cathode layer, a circuit is completed through the ionically conductive electrolyte completing the circuit. As long as hydrogen is pumped into the system, electricity will be generated.

SOFCs are electrochemical power sources that are fueled by hydrogen and produce no air pollutants, making them an attractive alternative to combustion-based power sources. The development of a hydrogen infrastructure to produce, store and transfer hydrogen is underway in numerous countries, driven by the global focus on transitioning to low-cost, renewable energy sources. The rise of fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) that possess longer ranges than battery-powered vehicles is leading to a vast expansion of hydrogen fueling stations around the world; developing safe, lightweight, and energy-efficient on-board hydrogen storage systems will make fuell cell-based vehicle technology more cost-effective and widespread, and researchers are actively pursuing new advanced materials-based solutions. For example, prototype fuel cell anodes incorporating graphene balls have been shown to increase the volumetric energy of the cell by 27.8%.

Hydrogen Storage

Hydrogen can easily be generated from renewable energy sources, making it a primary focus in the area of alternative energy research. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and is produced from various sources such as fossil fuels, water and renewables. As a fuel source, hydrogen is nonpolluting and forms water as a harmless byproduct during use; it can be stored indefinitely, far outlasting the energy storage capacity of lithium-ion batteries. The challenges associated with the use of hydrogen as a form of energy include developing safe, compact, reliable, and cost-effective hydrogen storage and delivery technologies. Currently, hydrogen can be stored in these three forms: compressed hydrogen, liquid hydrogen, and chemical storage in the form of metal hydrides. Solid-state hydrogen storage

Hydrogen has enormous potential for storing the reserve energy that solar and wind power generates--a flow that can fluctuate greatly based on time of day and other environmental factors--thereby stabilizing the load on electrical grids with the ability to store and distribute energy at the gigawatt-hour and terawatt-hour scales, far more than the capabilities of current battery technology. Researchers are pinpointing new advanced materials for physical storage such as ionic liquids, carbon-based sorbents, high surface-area nanomaterials such as carbon, boron nitride, or MoS2/TiS2 nanotubes, and 3D printed metalorganic framewords (MOFs).

Hydrogen can easily be generated from renewable energy sources, making it a primary focus in the area of alternative energy research. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and is produced from various sources such as fossil fuels, water and renewables. As a fuel source, hydrogen is nonpolluting and forms water as a harmless byproduct during use; it can be stored indefinitely, far outlasting the energy storage capacity of lithium-ion batteries. The challenges associated with the use of hydrogen as a form of energy include developing safe, compact, reliable, and cost-effective hydrogen storage and delivery technologies. Currently, hydrogen can be stored in these three forms: compressed hydrogen, liquid hydrogen, and chemical storage in the form of metal hydrides. Solid-state hydrogen storage

Hydrogen has enormous potential for storing the reserve energy that solar and wind power generates--a flow that can fluctuate greatly based on time of day and other environmental factors--thereby stabilizing the load on electrical grids with the ability to store and distribute energy at the gigawatt-hour and terawatt-hour scales, far more than the capabilities of current battery technology. Researchers are pinpointing new advanced materials for physical storage such as ionic liquids, carbon-based sorbents, high surface-area nanomaterials such as carbon, boron nitride, or MoS2/TiS2 nanotubes, and 3D printed metalorganic framewords (MOFs).

Battery Technology

Battery technology has grown rapidly due to the wide-spread use of rechargeable solid-state batteries in computers, vehicular applications and portable electronics. Batteries contain a number of voltaic cells; each voltaic cell consists of two half cells connected in series by a conductive electrolyte containing anions and cations. The type of chemical reaction that can be used in an electrochemical cell is known as an reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction in which one chemical species gives electrons to another. Anions, which are negatively charged ions, oxidize at the anode in the reduction-oxidation reaction, while cations, positively charged ions, are reduced at the cathode. By controlling the flow of ions between the two species through separation, battery engineers make devices in which virtually all of these electrons can be made to flow through an external circuit, thereby converting most of the chemical energy to electrical energy during the discharge of the cell.

Battery technology has grown rapidly due to the wide-spread use of rechargeable solid-state batteries in computers, vehicular applications and portable electronics. Batteries contain a number of voltaic cells; each voltaic cell consists of two half cells connected in series by a conductive electrolyte containing anions and cations. The type of chemical reaction that can be used in an electrochemical cell is known as an reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction in which one chemical species gives electrons to another. Anions, which are negatively charged ions, oxidize at the anode in the reduction-oxidation reaction, while cations, positively charged ions, are reduced at the cathode. By controlling the flow of ions between the two species through separation, battery engineers make devices in which virtually all of these electrons can be made to flow through an external circuit, thereby converting most of the chemical energy to electrical energy during the discharge of the cell.

Lithium-ion technology dominates the current scene of consumer electronics such as cell phones, laptops, and electric vehicles. Typically composed of a liquid lithium compound electrolyte, graphite anode, and cathode materials such as lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NCM), these batteries are high performance, portable, and rechargeable. However, dangers associated with the flammability of the liquid electrodes and the performance limitations of the materials has spurred the search for better technologies. Some under investigation include vanadium flow, solid state thin-film, lithium sulfur, flexible lithium polymer, and sodium ion.

Modifications to existing battery architectures include using pure lithium metal electrodes, which can store more ions than graphite, or altering the composition of NMC by increasing the nickel and decreasing the cobalt contents, which yields greater efficiency for use in long-range electric vehicle batteries. Lithium-sulfur batteries have three to five times the capacity of traditional lithium ion cells, in addition to being cheaper to manufacture, more environmentally friendly. Metal mesh membranes are under investigation for use in grid-scale installations.

Wind Energy

Converting wind energy into electricity using various blade and turbine systems has been utilized since the mid-1970s when tax incentives were written in many states to encourage public utilities to purchase the power generated. Many of these earlier systems failed to deliver efficient energy and were only financially viable as tax shelters. More recently advanced materials, particularly advanced ceramics such as yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and composites, have played a part in the development of lighter, less costly and more efficient wind turbines. Additionally, the decades of experience with wind as an energy source has allowed for the design of better overall wind generator farms placed in strategically determined locations including offshore wind farms. With a generating capacity of 630 MW, the London Array in United Kingdom is the largest offshore wind farm in the world. Between 2009 and 2016, installed project costs for new wind farms dropped 33%, while also generating more electricity per turbine; the U.S. DOE estimates that by the rise of the use of supercomputing and accelerating energy science R&D efforts will cut the cost of wind energy in half by 2030.

The Nuclear Power Dilemma

One source of energy that is entirely free from greenhouse gas emissions is nuclear energy, power generated by the fission of enriched radioactive isotopic materials. Nuclear generators are the single greatest source of energy that in no way impacts global warming. However, all nuclear fission systems generate some form of radioactive waste which must be disposed of. Given the lengthy half-life of the waste materials, "disposal" actually means perpetual storage. The green technology goal of sustainable growth dictates that human activity not produce waste products that cannot be perpetually reused or recycled; the waste generated by nuclear power not only violates this standard but also poses risks to the health and safety of individuals and the environment. Nuclear fusion, a long-sought alternative to fission, would be an inexhaustible, sustainable, and zero-carbon source of energy which does not release emissions or long-term waste; researchers at MIT have made great strides in laying the groundwork for commercialization of this tecnnology.

One source of energy that is entirely free from greenhouse gas emissions is nuclear energy, power generated by the fission of enriched radioactive isotopic materials. Nuclear generators are the single greatest source of energy that in no way impacts global warming. However, all nuclear fission systems generate some form of radioactive waste which must be disposed of. Given the lengthy half-life of the waste materials, "disposal" actually means perpetual storage. The green technology goal of sustainable growth dictates that human activity not produce waste products that cannot be perpetually reused or recycled; the waste generated by nuclear power not only violates this standard but also poses risks to the health and safety of individuals and the environment. Nuclear fusion, a long-sought alternative to fission, would be an inexhaustible, sustainable, and zero-carbon source of energy which does not release emissions or long-term waste; researchers at MIT have made great strides in laying the groundwork for commercialization of this tecnnology.

Geothermal Energy

Another possible solution to the problem of global warming is geothermal energy, or power generated by heat stored in the earth from the formation of the planet, the radioactive decay of minerals, and solar energy absorbed at the surface. Geothermal energy has been used for bathing since Paleolithic times, in the form of hot springs and other natural formations, and for living space heating since ancient Roman times. The earliest industrial exploitation of geothermal energy began in 1827 with the use of geyser steam to extract boric acid from volcanic mud in Larderello, Italy. Lord Kelvin invented the heat pump in 1852, and Heinrich Zoelly had patented the idea of using it to draw heat from the ground in 1912. But it was not until the late 1940s that the geothermal heat pump was successfully implemented. The 1979 development of polybutylene pipe greatly augmented the heat pump's economic viability.

Today geothermal energy is now better known for generating electricity. Direct geothermal heating is used for district heating, space heating, spas, desalination, industrial processes, and agricultural applications. The Earth's internal heat naturally flows to the surface by conduction at a rate of 44.2 terawatts, (TW,) and is replenished by radioactive decay of minerals at a rate of 30 TW. These power rates are more than double humanity's current energy consumption from all primary sources, but most of it is not recoverable. In addition to heat emanating from deep within the Earth, the top ten metres of the ground accumulates solar energy (warms up) during the summer, and releases that energy (cools down) during the winter.

Geothermal power is cost effective, reliable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly, but has historically been limited to areas near tectonic plate boundaries. Recent technological advances have dramatically expanded the range and size of viable resources, especially for applications such as home heating, opening a potential for widespread exploitation. Geothermal wells release greenhouse gases trapped deep within the earth, but these emissions are much lower per energy unit than those of fossil fuels. As a result, geothermal power has the potential to help mitigate global warming if widely deployed in place of fossil fuels.

Sustainable Development

Goal: Reduce overall energy usage, contamination of our environment, and consumer-generated waste

The realization that increase in consumption after World War II was causing an equally massive generation of waste products for which there was little technology or public policy to address spawned the original environmental movement with its emphasize on reducing ground, air and water pollution. As policies and technologies were created to address pollution, it became clear that the real long term goal must be to ultimately establish a fully sustainable planet: one that could perpetually sustain itself in its present form through better management of its resources. This would require efforts on several technological fronts. First, products needed to be designed and built with an eye towards eliminating wasteful materials used and the reuse and recycling of the materials that are used once the product has exhausted its useful life. Second, reliance on difficult to replenish resources from timber to oil needed to be drastically reduced through the development of new recyclable advanced materials.

Additive Manufacturing & 3D Printing

Additive Manufacturing (3D printing, Rapid Prototyping) is revolutionizing the process of producing industrial components for the aerospace, automotive, biomedical devices, dental, consumer electronics, and defense industries. With the aid of 3D CAD modeling software, complex metallic and ceramic forms can be designed and fabricated by building layers from the "ground up." This technique significantly reduces the time require to fabricate parts and the amount of waste material typically generated by traditional subtractive methods such as casting. Industries are increasingly recognizing the potential of additive manufacturing technology to not only maximize efficiency and cost-effectiveness of their production processes but also to further the sustainability goals of green technology.

Energy Conservation

Energy conservation is essential both to minimizing the impact of our current usage of fossil fuels, and to make the complete replacement of those fuels with renewable energy sources possible. Energy needs can be reduced through the use of more efficient devices that require less power to achieve the same purpose, as when light emitting diodes or improved fluorescent bulbs replace traditional incandescents. These technologies will only continue to expand in use as material innovations allow for more applications and lower costs. Buildings can be designed to demand less energy by using more effective insulation, maximizing the use of natural lighting, and using passive solar heating and cooling. Automotive manufacturers can improve vehicle efficiency through the use of next generation materials such as metal foams that allow for lighter vehicles with better mileage without compromising the structure of the vehicle.

The advent of "smart" home technology and the Internet of Things (IoT) has brought about new ways of increasing energy efficiency and consumption through automation. Smart thermostats, for example, can adjust the temperature of a home when not in use, thereby decreasing the overall amount of electricity required to heat the home. Wireless sensor networks , RIFD, biometrics, and AI are all contributing to advancements in reducing emissions, stabilizing the electricity grid, environmental conservation, and driverless transportation.

LED (Solid State) Lighting

For hundreds of years, lighting sources were limited first to incandescent bulbs, devices which produce light by converting electricity into heat and then light, then fluorescent bulbs, which produce light via a chemical reaction between a noble gas and mercury vapor. The invention of solid-state lighting in the 1960s revolutionized lighting technology, eliminating the need for filaments, plasma, or gas, and instead utilizing semiconductors to produce light in a dramatically more efficient manner.

The paradigm of solid state lighting is the light-emitting diode (LED). LEDs combine a p-type and n-type semiconductor materials and convert electrical energy directly into light at the junction between them, releasing photons when the electrons and holes combine. This process of light production is more efficient because it both requires less energy input and reduces or eliminates wasted energy from the release of heat. Less energy means a smaller environmental footprint, reducing the demand from power plants and decreasing greenhouse gas emission.

In addition to producing light more efficiently, LEDs produce higher quality light. The color (or emission) of the light produced depends on the semiconductor materials, which may be combined with dopants or phosphors, and a wide range of colors can be achieved. White light, however, was notoriously difficult to achieve during the early stages of LED development. Poor quality white light could be produced by combining red, green, and yellow LEDs, but this method was highly inefficient and thus cost-prohibitive. A breakthrough came with the development of truly white LEDs that combine a blue LED based on gallium nitride (GaN) with a yellow phosphor, Ce:YAG. This discovery allowed white light-producing LEDs to become commercially viable, replacing traditional incandescent light bulbs in the consumer market.

LEDs are also the source of light in liquid-crystal display (LCD) screens of various devices such as televisions, computer monitors, and instrument panels. These screens require a back light or reflector to illuminate the screen. While these devices were the standard for decades, the development of next-generation solid state lighting again revolutionized lighting technology in a way that continues to develop. Second-generation LEDs utilize organic materials as the semiconducting emission layer. Known as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), these devices are more efficient and environmentally friendly than conventional LEDs, in addition to being less expensive to produce based on the materials. OLEDs produce thinner, flexible displays with high contrast and color intensity, producing darker blacks, making them the preferred light source for flat-panel televisions, smartphones, computer monitors, and portable gaming units. The cathode material is typically indium tin oxide (ITO), a transparent ceramic. Despite their advantages, OLEDs suffer from lifespan issues, as the organic compounds can degrade over time.

The most recent generation of solid state lighting utilizes quantum dots, semiconductor nanoparticles that have tunable optical properties. QLEDs produce the highest quality color and contrast and are the pinnacle in terms of power efficiency, picture quality, and production price.

Environmental Remediation

Materials innovations are essential for reducing and remediating pollution. One of the most successful means of reducing air pollution has been the requirement that catalytic converters be installed in automobiles to reduce the release of nitrogen and sulfur-containing side products of fuel production. The catalysis that occurs in these devices requires expensive precious metals, and catalyst support materials that maximize effectiveness while limiting the amount of these metals required. Catalyst supports in these devices are typically high-performance ceramics that can withstand the heat of an engine. Similar ceramic materials may be used in filtration devices for removing pollutants from air streams or contaminated water.

In addition to removing polluting compounds after the environment has been contaminated, or capturing them at the site of production, it is possible to prevent the possibility of pollution from some sources by using less hazardous materials. Toxic metals such as cadmium, arsenic, and lead are found widely in electronics, while dangerous synthetic organic compounds are found in or used in making a wide variety of products. Replacing these with nontoxic alternatives prevents their release into the environment when the products containing them are eventually disposed of. The use of lead has already been substantially reduced through the use of lead-free solders in electronics, and similar improvements can be made to reduce contamination with other toxic compounds.

Advanced high surface area nanomaterials are playing an increasing role in environmental remediation. Nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) in particular is highly efficient in removal of pollutants from soil, sediments, and water sources; titanium dioxide nanoparticles have been shown to convert contaminants to less toxic compounds via photocatalysis. Other high performance materials include bimetallic nanoscale particles (BNPs) composed of elemental iron or another metal with a catalyst metal such as palladium, and highly porous crystalline materials such as zeolites and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

Reducing Consumer Waste

Currently, a large percentage of consumer products are either single-use or have short lifespans, and end their lives in a landfill where they will not biodegrade. Materials of particular concern include plastics and a variety of materials used in electronics. Plastics are entirely synthetic polymers that degrade extremely slowly in the environment, while the inorganic materials used in electronics are at best simply tied up in an unusable state in a landfill, and at worst leach out of dump sites and poison the surrounding environment.

Currently, a large percentage of consumer products are either single-use or have short lifespans, and end their lives in a landfill where they will not biodegrade. Materials of particular concern include plastics and a variety of materials used in electronics. Plastics are entirely synthetic polymers that degrade extremely slowly in the environment, while the inorganic materials used in electronics are at best simply tied up in an unusable state in a landfill, and at worst leach out of dump sites and poison the surrounding environment.

One major way to reduce plastic and e-waste is to recycle these materials, but current recycling techniques are often energy-intensive and not always economically viable. In some cases, this problem can be addressed by designing products with reuse or recycling in mind, and improving recycling methods. Additionally, alternate materials that are renewable and biodegradable can be used in place of polluting plastics and scarce inorganic elements. Improved bioplastics can be developed to replace plastics that can not be easily recycled, while further development of organic electronics could reduce the need for traditional electronics materials. Scientists are investigating enzymes that can digest synthetic polymers such as those used in single-use plastic beverage bottles, a a major step towards developing biobased plastic recycling methods.

Advanced Materials for Green Technology

Unlike the technological waves in past decades, green technologies are almost entirely focused on materials science. Making solar energy both economically and environmentally viable for widespread usage, for example, will require more energy efficient photovoltaic devices that contain fewer scarce or toxic elements, better heat resistant coatings and thermal transfer materials for solar thermal plants, and commercially viable and cost-effective energy storage technologies, all of which require advancements and innovations in materials science.

New Materials

Elements on the periodic table such as copper, tin, iron and carbon are stepping aside in favor of less common metals, such as zirconium, yttrium, tellurium and the 14 elements that make of the group of metals known as the rare earths.

In addition to the use of new metallic elements is the combination of these less common metals with common metals to form new super alloys with unique properties, such as scandium-aluminum, which can combine lightness, extreme strength and high temperature and corrosion tolerance in a single material. Another example would be newly developed metal carbides that yield super hard and corrosive resistant materials with interesting properties. Similarly, the use of glass and ceramics in functional components of electronics and energy efficient systems is giving way to the use of crystal structures, semiconductors, and superconducting materials.

New Techniques

When Thomas Edison first did his experiments with electricity and the electronic equipment it could power, he wasn't concerned with how much copper was required to carry a circuit or the amount of power being used. As electronics became smaller and more complicated, the company he built, General Electric, became very concerned with reducing the scale and volume of metal used. Thinner conductive and semi-conductive layers and wires were necessary. Until the 1970s, this was accomplished using electroplating of metallic solutions, such as metal chlorides combined with etching technologies. Now, thin film coatings do not require electroplating and can be achieved using sputtering targets and high purity foils.

The fabrication of functional layers of materials at the nanoscale can now be accomplished by converting the material into a plasma-like chemical vapor which deposits the material on a substrate. Modern hand-held electronics rely on thin film deposition to achieve their small size.

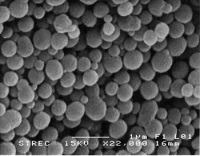

Nanotechnology & Nanomaterials

Nanotechnology is playing an increasing role in solving the world energy crisis. Platinum nanoparticles are ideal candidates as a novel technology for low-platinum automotive catalysts. Lanthanum nanoparticles, cerium nanoparticles, strontium carbonate nanoparticles, manganese nanoparticles, manganese oxide nanopowder, nickel oxide nanopowder and several other nanoparticles are finding application in the development of small cost-effective solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). Platinum nanoparticles are being used to develop small proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMs). lithium nanoparticles, lithium titanate nanoparticles and tantalum nanoparticles will be found in next generation lithium ion batteries. Ultra high purity silicon nanoparticles are being used in new forms of solar cells. Thin film deposition of silicon quantum dots on the polycrystalline silicon substrate of a photovoltaic cell increases voltage output as much as 60% by fluorescing the incoming light prior to cap ture.

ture.

Silicon nanoparticles have been shown to dramatically expand the storage capacity of lithium ion batteries without degrading the silicon during the expansion/contraction cycle that occurs as power is charged and discharged. Silicon has long been known to have an excellent affinity for storage of positively charged lithium cations making them ideal candidates for next generation lithium ion batteries. Unfortunately, the quick degradation of silicon storage units has made them commercially unfeasible for most applications. Silicon nanowires however, cycle without significant degradation and present the potential for use in batteries with greatly expanded storage times.

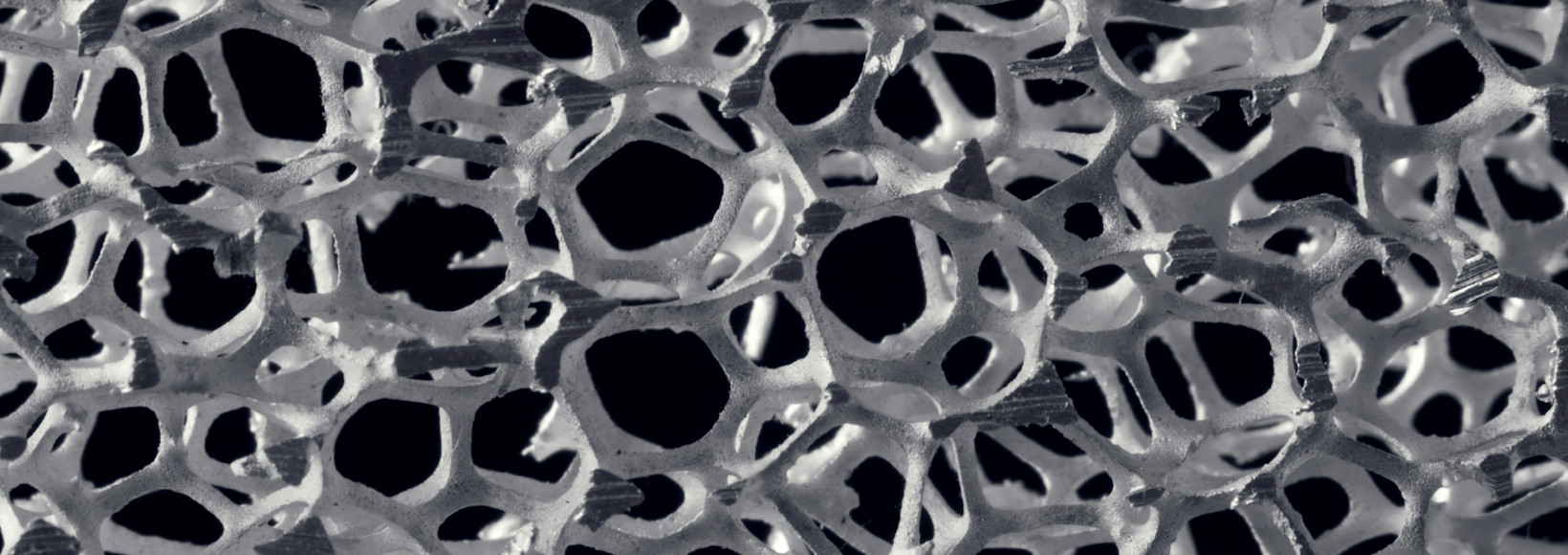

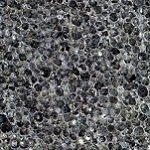

Metallic & Ceramic Foams

Metallic and ceramic foams are becoming increasingly important in the treatment of environmental pollutants. Foams are cellular structures consisting of a solid metal or ceramic material containing a large volume fraction of gas-filled pores. The pores can be sealed, closed-cell foam, or they can form an interconnected network, open-cell foam. The defining characteristic of these foams is a very high porosity, typically 75-95% of the volume consisting of void spaces. Metallic and ceramic foams are often used in green technology applications because the high surface area facilitates the adsorption of environmental pollutants and other chemicals. They can also be used for thermal and acoustic insulation, and as a substrate for other catalysts requiring large internal surface area.

Metallic and ceramic foams are becoming increasingly important in the treatment of environmental pollutants. Foams are cellular structures consisting of a solid metal or ceramic material containing a large volume fraction of gas-filled pores. The pores can be sealed, closed-cell foam, or they can form an interconnected network, open-cell foam. The defining characteristic of these foams is a very high porosity, typically 75-95% of the volume consisting of void spaces. Metallic and ceramic foams are often used in green technology applications because the high surface area facilitates the adsorption of environmental pollutants and other chemicals. They can also be used for thermal and acoustic insulation, and as a substrate for other catalysts requiring large internal surface area.

Green Technology Products

Below is only a limited selection of the full catalog of products that American Elements manufactures for the green technology and alternative energy sectors. If you do not see a material you're looking for listed, please search the website or contact customerservice@americanelements.com.