About Helium

Using a spectrometer to analyze the chromosphere of the sun during a solar eclipse in 1868, French astronomer Jules Janssen noticed an unusual yellow line in the spectrum that he suspected indicated the presence of a yet-undiscovered element. Several months thereafter, English chemists Joseph Norman Lockyer and Edward Franklin observed the same spectral line in sunlight and came to the same conclusion; the two proposed the name “Helium” for the element after Helios, the Greek god of the sun, appropriate for the first element to be discovered in space rather than on earth. Scottish chemist William Ramsay was the first to successfully isolate the element in 1895 by treating a sample of the uranium ore cleveite, thereby proving its existence on earth.

Limited to the scope of the planet, helium is a relatively scarce element, produced only in via the radioactive decay of elements such as uranium and thorium. It is the sixth most abundant gas in the atmosphere at 5.2ppm and one of the only elements light enough to possess escape velocity, rising and exiting the atmosphere at a rate roughly equal to its formation on earth. In space, however, helium is far more prevalent; it is the second most abundant element in the universe after hydrogen, making up 24% of its total observable mass, and is primarily produced in the cores of hydrogen-burning stars that fuse protons into helium nuclei to produce light and heat.

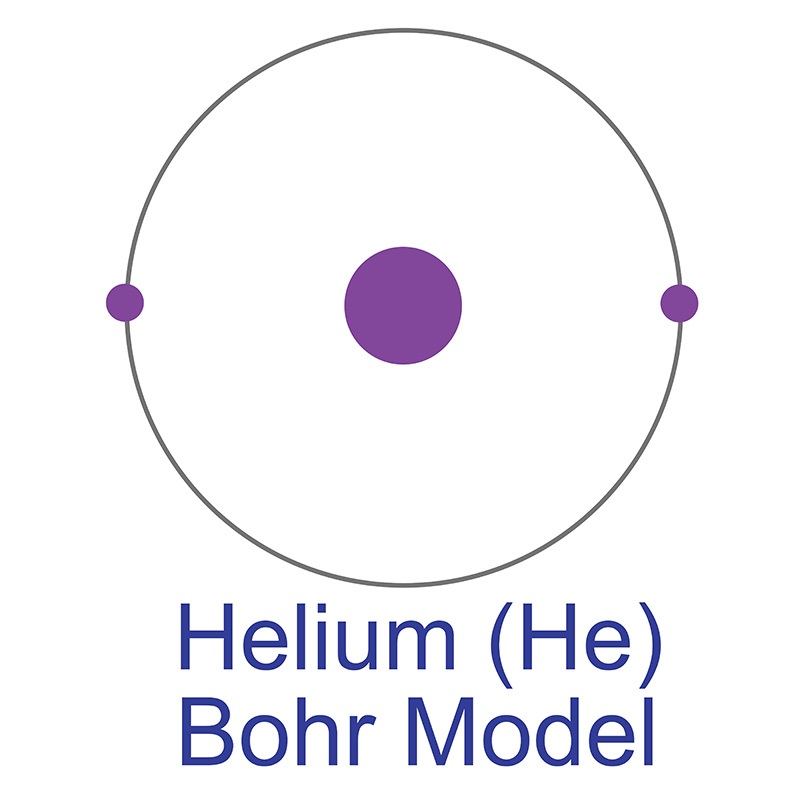

Helium remained unknown by scientists for so long due to its extreme chemical inertness, making it difficult to detect via conventional methods. This inertness is characteristic of the elements known as “noble gases” (Group 18 on the periodic table, which includes neon and argon), whose extreme stability and unwillingness to react with other elements is due to the completeness of their outer valence shells. Odorless, colorless, and nontoxic, helium is the lightest of the noble gases, and the second lightest of all elements in the universe after hydrogen. 99.999% of all helium atoms exists as stable isotope helium-4, composed of two protons, two neutrons, and two electrons in a single shell. This structure yields the most stable and inert element on the periodic table, a monoatomic gas that always exists in pure elemental form in its natural state. Neon is the only element other than helium that has never been observed to bond with other elements in stable compounds; however, at temperatures close to absolute zero and under extreme pressure, helium can form unstable excimer molecules with elements like sodium, fluorine, and nitrogen. The helium-4 nucleus on its own is known as an alpha particle, the particle emitted in alpha-type radioactive decay. Approximate 0.0001% of natural helium is composed of its other stable isotope, helium-3, the nucleus of which has one neutron and is referred to as a helion. The existence of helium-3 was proven by Luis W. Alvarez and Robert Cornog at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 1939. Seven other highly unstable isotopes are known; Helium-9, for example, has a half-life of 7 zeptoseconds, or seven sextillionths of a second.

Helium has the lowest solubility in water of any known gas and the lowest melting point of all elements on the periodic table; in fact, it is the only element that cannot be effectively solidified by merely lowering its temperature, as it remains liquid in form down to nearly absolute zero. Close to those temperatures, helium form a superfluid, a quantum state first discovered by Russian physicist Pyotr Kapitsa and John F. Allen in 1937: with almost zero viscosity or entropy, the fluid exhibits superconductivity and can flow up and over the walls of containers, defying the laws of gravity and surface tension, and can pass through nanoscale holes that would normally be impermeable to the gas. At 0.95K, helium can be transformed into a so-called supersolid or quantum solid by applying 25 atmospheres of pressure; to achieve the same result at room temperature requires 114,000 atmospheres of pressure, over 100 times greater than pressure experienced at the deepest point on the ocean floor. The unusual crystalline structure of solid helium exhibits an internal frictionless flow of atoms that impart properties like high compressibility and reversible plasticity.

Billions of cubic feet of helium are produced for commercial consumption each year, primarily from the natural gas wells between Amarillo, Texas and Hugoton, Kansas in the central United States. Helium comprises up to 7% of natural gas deposits and can be isolated from methane and other contaminants via the process of fractional distillation. Both liquid and gaseous helium play a role in the commercial sphere. Helium was first liquefied by Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes in 1913, earning him the Nobel Prize, and approximately 25% of helium’s current commercial use is in liquid form for cryogenic refrigeration. Because helium remains in liquid form even at extremely low temperatures, it is used to cool superconducting wires in high-powered magnets used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and large particle accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider at CERN; it also serves as a heat-transfer medium for gas-cooled nuclear reactors thanks to its transparency to neutrons and high thermal conductivity. Buoyant in air, helium gas has had well-known use in ballooning since the early 20th century, eventually replacing hydrogen due to the latter’s extreme flammability (as demonstrated by the infamous 1937 Hindenburg airship disaster). The first gas lasers employed a combination of helium and neon, and the air tanks of scuba divers substitute helium for nitrogen to prevent decompression sickness due to helium’s lower blood solubility. Helium has applications in gas chromatography, industrial gas leak detection using helium mass spectrometers, and geological dating of thorium and uranium-containing rocks.

By far the most prominent commercial use for helium gas is providing an inert atmosphere for arc welding and semiconductor component fabrication, particularly during growth of high purity silicon and germanium single crystals. Other emerging roles in advanced technology for helium include allowing further investigation into the properties of quantum superfluids and supersolids, serving as a plasma source in plasma transistors that can operate at temperatures higher than silicon-based transistors, rocket propulsion from the fusion of helium-3 with deuterium, and using spin-polarized helium-3 beams for medical imaging and materials analysis.

Helium Properties

Helium is a Block S, Group 18, Period 1 element. The number of electrons in each of Helium's shells is 2 and its electronic configuration is 1s2. In its elemental form helium's CAS number is 7440-59-7. The helium atom has a covalent radius of 28.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 140.pm. Commercial helium is extracted from natural gas. Helium was discovered by Pierre Janssen and Norman Lockyer in 1868. It was first isolated by William Ramsay, Per Teodor Cleve and Abraham Langlet in 1895.

Helium is a Block S, Group 18, Period 1 element. The number of electrons in each of Helium's shells is 2 and its electronic configuration is 1s2. In its elemental form helium's CAS number is 7440-59-7. The helium atom has a covalent radius of 28.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 140.pm. Commercial helium is extracted from natural gas. Helium was discovered by Pierre Janssen and Norman Lockyer in 1868. It was first isolated by William Ramsay, Per Teodor Cleve and Abraham Langlet in 1895.

Helium information, including technical data, properties, and other useful facts are specified below. Scientific facts such as the atomic structure, ionization energy, abundance on Earth, conductivity, and thermal properties are included.

Health, Safety & Transportation Information for Helium

Helium is not toxic and is chemically inert, and thus poses minimal environmental or health threats. At room temperature, helium is typically only harmful when its presence leads to displacement of oxygen in the air, creating potential for asphyxiation. Liquid helium is extremely cold; therefore skin contact with the liquid can cause frostbite, and should be avoided.

| Safety Data | |

|---|---|

| Material Safety Data Sheet | MSDS |

| Signal Word | Warning |

| Hazard Statements | H280 |

| Hazard Codes | N/A |

| Risk Codes | N/A |

| Safety Precautions | N/A |

| RTECS Number | MH6520000 |

| Transport Information | UN 1046 2.2 |

| WGK Germany | 3 |

| Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling (GHS) |

|

Helium Isotopes

Helium has two stable isotopes: 3He and 4He.

| Nuclide | Isotopic Mass | Half-Life | Mode of Decay | Nuclear Spin | Magnetic Moment | Binding Energy (MeV) | Natural Abundance (% by atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2He | 2.015894(2) | N/A | p to 2H | 0+(#) | N/A | N/A | - |

| 3He | 3.0160293191(26) | Stable | - | 1/2+ | -2.127624 | 7.718058 | 0.000137 |

| 4He | 4.00260325415(6) | Stable | - | 0+ | 0 | 28.295673 | 99.999863 |

| 5He | 5.01222(5) | 700(30)E-24 s | n to 4He | 3/2- | N/A | 27.405672 | - |

| 6He | 6.0188891(8) | 806.7(15) ms | ß- to 6Li | 0+ | N/A | 29.269108 | - |

| 7He | 7.028021(18) | 2.9(5)E-21 s [159(28) keV] | n to 6He | (3/2)- | N/A | 28.824289 | - |

| 8He | 8.033922(7) | 119.0(15) ms | ß- to 8Li; ß- + n to 7Li | 0+ | N/A | 31.407892 | - |

| 9He | 9.04395(3) | 7(4)E-21 s | n to 8He | 1/2(-#) | N/A | 30.258837 | - |

| 10He | 10.05240(8) | 2.7(18)E-21 s | 2n to 8He | 0+ | N/A | 30.338511 | - |