About Oxygen

One might think that the ubiquity and vital importance of oxygen would facilitate its early and easy discovery, but this was not the case. True, for many centuries of human history, the necessity of some aspect of air to the processes of combustion and respiration was intuited and articulated by scholars, yet until the late eighteenth century, a full theoretical understanding of the underlying chemistry of these processes remained elusive.

A significant barrier to this understanding was phlogiston theory, an early chemical theory that claimed all combustible materials contained phlogiston, and during burning this substance was released. The observation that air contained components that both supported and failed to support combustion had been made, but phlogiston theory dictated that this was due to a limited capacity of air to absorb phlogiston. Both Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Joseph Priestley isolated a component of air that supported both combustion and respiration for longer than ordinary air, with the former referring to it as “fire air” and the latter “dephlogisticated air”, both assuming that what they had found was the substance that combined with phlogiston during combustion. This gas, of course, was oxygen, and Priestley is typically given credit for its discovery; though Scheele isolated his “fire air” first, in 1771, Priestley was first to publish his method of synthesis, which he did in 1774. It took a third chemist, Antoine Lavoisier, to recognize that the newly discovered gas was in fact a new element; he published the first correct explanation of combustion in 1777. Though correct in his dismissal of phlogiston, Lavoisier developed his own mistaken theory stating that all acids contained this new element, and therefore named the element from the Greek roots oxys, acid, and genes, producer. By the time this belief was proven incorrect, the name oxygen had stuck.

It is understandable that early chemists were baffled by oxygen, as they had little experience with elements that came in such an astounding array of forms. A strong oxidizing agent greedy for electrons, oxygen will react with nearly any element given sufficiently high temperatures. Oxygen is found in water and most organic compounds, and its ability to form both single and double bonds, its presence in many polyatomic ions, and its tendency to form complexes with transition metals such as iron all serve to further expand the list of oxygen-containing substances. Major ores of iron, zinc, and aluminum are all oxides, as is the quicklime used in mortar and concrete, the carbon dioxide produced by aerobic respiration, and common silica sand.

In its compound forms, the uses of oxygen are nearly limitless, but even in the form of the pure element, it has many applications. The most stable and common allotrope of oxygen is the O2 we breathe. Pure oxygen gas is traditionally extracted from liquefied air through the fractional distillation; it is left behind in liquid form after nitrogen has evaporated. Additionally, various molecular sieves including activated carbon, zeolites, and silica gel can be used to separate clean dry air, exploiting the differing affinities of nitrogen and oxygen for the filter material at varying pressures. This second method is often used for portable oxygen concentrators used by patients with respiratory ailments. Concentrated oxygen is additionally used for life support in aerospace and diving contexts. Pure oxygen finds use as rocket fuel, as a reagent in the chemical industry, and in metallurgy. In steel smelting, injecting pure oxygen removes sulfur impurities and excess carbon as oxides, while in oxy-fuel welding and metal welding, pure oxygen is used to produce an exceptionally hot flame.

Though common oxygen gas (O2) is known as an oxidizing agent, another form of oxygen is much more potent in this regard. Ozone, a molecule composed of three oxygen atoms, is also an extremely potent oxidizing agent. Ozone is produced in small amounts from molecular oxygen through a variety of processes, most commonly from the action of ultraviolet radiation on fossil fuel byproducts in the air, and from the electrolysis of air--ozone is responsible for the distinctive smell associated with lightning strikes. Ozone’s reactivity makes it toxic, but it decays to harmless oxygen, making it particularly useful for disinfection in contexts where any toxic residue would be unacceptable. It is regularly used to kill insects in grain, spores in food processing plants, and bacteria on food and surfaces. Increasingly, it is used as a replacement for chlorine bleach in producing fabrics and processing wood pulp to manufacture paper, usually in conjunction with another strong oxidizing agent, hydrogen peroxide. It also reacts with many water contaminants including metals, sulfides, nitrites, and complex organics, and can be used in water treatment plants to both kill biological agents and neutralize chemical toxins. Ozone’s instability requires that it be produced on site, rather than mass produced and transported. This is typically accomplished using high-voltage electrolysis of air, or through the use of ultraviolet ozone generators.

Oxygen Properties

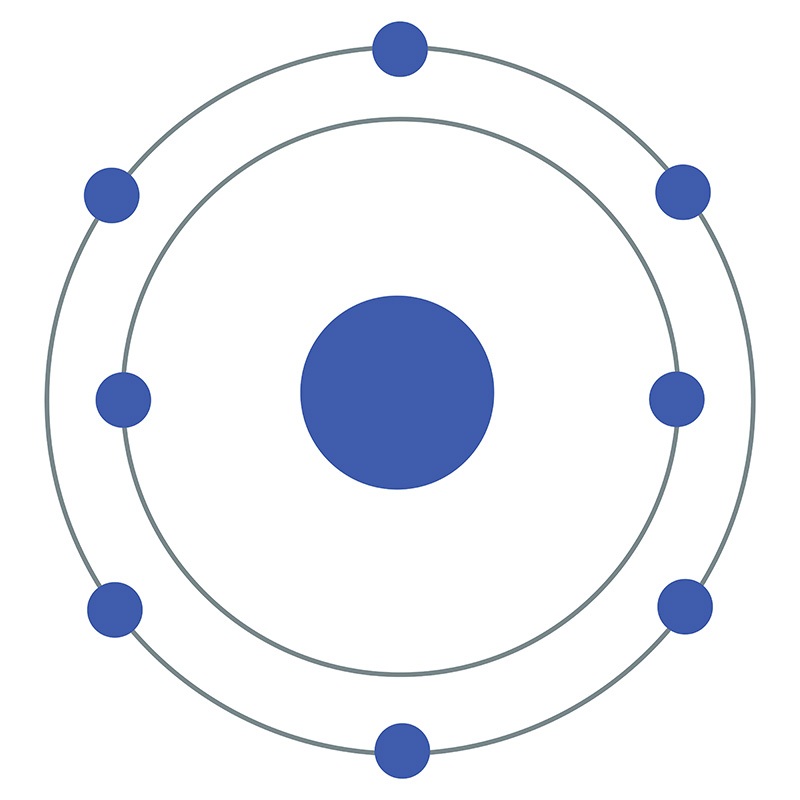

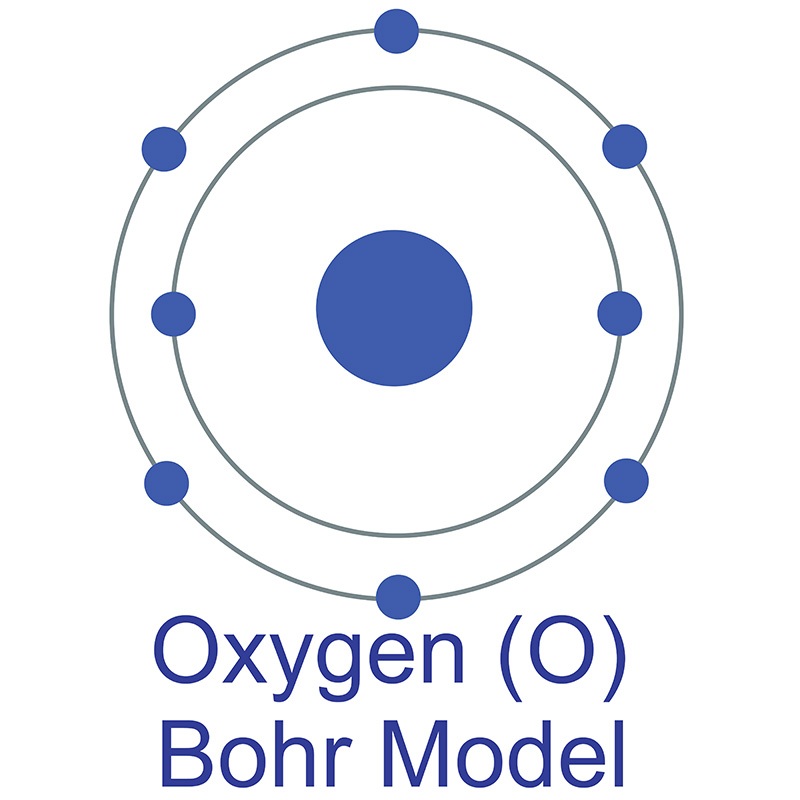

Oxygen is a Block P, Group 16, Period 2 element. Its electron configuration is [He]2s22p4 . The oxygen atom has a covalent radius of 66±2 pm and its Van der Waals radius is 152 pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7782-44-7, oxygen is colorless gas or a pale blue liquid. The name oxygen is derived from the Greek word oxys, meaning acid because, at the time of its naming, it was thought that acids required oxygen in their composition.

Oxygen is a Block P, Group 16, Period 2 element. Its electron configuration is [He]2s22p4 . The oxygen atom has a covalent radius of 66±2 pm and its Van der Waals radius is 152 pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7782-44-7, oxygen is colorless gas or a pale blue liquid. The name oxygen is derived from the Greek word oxys, meaning acid because, at the time of its naming, it was thought that acids required oxygen in their composition.

Oxygen information, including technical data, safety data and its high purity properties, research, applications and other useful facts are specified below. Scientific facts such as the atomic structure, ionization energy, abundance on Earth, conductivity and thermal properties are included.

Health, Safety & Transportation Information for Oxygen

Pure oxygen is highly reactive, and can react violently with common materials such as oil or grease. Almost all materials will burn vigorously in pure oxygen, including textiles, rubber, and metals, once a fire has been started. Some materials may catch fire spontaneously in an oxygen enriched environment. Care should be taken in oxygen-enriched environments to avoid producing sparks, and materials that may ignite spontaneously must be avoided. Materials for tanks, hoses, gaskets, and pressure regulators used with compressed oxygen must be certified as safe for this use.

| Safety Data | |

|---|---|

| Material Safety Data Sheet | MSDS |

| Signal Word | Danger |

| Hazard Statements | H270-H280 |

| Hazard Codes | 0 |

| Risk Codes | 8 |

| Safety Precautions | N/A |

| RTECS Number | RS2060000 |

| Transport Information | UN 1072 2.2 |

| WGK Germany | nwg |

| Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling (GHS) |

|

Oxygen Isotopes

Oxygen has three stable isotopes: 16O, 17O and 18O.

| Nuclide | Isotopic Mass | Half-Life | Mode of Decay | Nuclear Spin | Magnetic Moment | Binding Energy (MeV) | Natural Abundance (% by atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12O | 12.034405(20) | 580(30)E-24 s [0.40(25) ] | 2p to 10C; p to 11N | 0+ | N/A | 56.29 | - |

| 13O | 13.024812(10) | 8.58(5) ms | ß+ to 13N; ß+ + p to 12C | (3/2-) | N/A | 73.69 | - |

| 14O | 14.00859625(12) | 70.598(18) s | EC to 14N | 0+ | N/A | 96.67 | - |

| 15O | 15.0030656(5) | 122.24(16) s | EC to 15N | 1/2- | 0.719 | 109.41 | - |

| 16O | 15.99491461956(16) | STABLE | - | 0+ | 0 | 125.87 | 99.757 |

| 17O | 16.99913170(12) | STABLE | - | 5/2+ | -1.8938 | 129.29 | 0.038 |

| 18O | 17.9991610(7) | STABLE | - | 0+ | 0 | 137.37 | 0.205 |

| 19O | 19.003580(3) | 26.464(9) s | ß- to 19F | 5/2+ | N/A | 141.72 | - |

| 20O | 20.0040767(12) | 13.51(5) s | ß- to 20F | 0+ | N/A | 148.87 | - |

| 21O | 21.008656(13) | 3.42(10) s | ß- to 21F | (1/2,3/2,5/2)+ | N/A | 153.22 | - |

| 22O | 22.00997(6) | 2.25(15) s | ß- to 22F; ß- + n to 21F | 0+ | N/A | 160.37 | - |

| 23O | 23.01569(13) | 82(37) ms | ß- + n to 22F; ß- to 23F | 1/2+# | N/A | 162.86 | - |

| 24O | 24.02047(25) | 65(5) ms | ß- + n to 23F; ß- to 24F | 0+ | N/A | 166.28 | - |

| 25O | 25.02946(28)# | <50 ns | Unknown | (3/2+)# | N/A | 165.97 | - |

| 26O | 26.03834(28)# | <40 ns | ß- to 26F; n to 25O | 0+ | N/A | 165.67 | - |

| 27O | 27.04826(54)# | <260 ns | Unknown | 3/2+# | N/A | 164.43 | - |

| 28O | 28.05781(64)# | <100 ns | Unknown | 0+ | N/A | 164.12 | - |