About Iron

As the major component of Earth’s core and the fourth most common element in the crust, iron is the most common element on the planet. Iron is a transition metal that has been known since ancient times, though meteoric iron was the only source of the element in metallic form until the widespread adoption of iron smelting techniques that began around 1500 BCE, a development that launched the period of history often termed the Iron Age. Producing iron metal from ore requires higher temperatures than could be achieved with the primitive furnaces used to produce bronze and pottery, and this along with the skill required to produce functional iron objects meant that iron working was a substantial technological advancement.

Though truly pure metallic iron is actually quite soft, producing the metal from ore results in the inclusion of carbon, which substantially alters the properties of the material. The earliest iron products were made from wrought iron, which generally contained less than one percent carbon. This product was tough, malleable, ductile, easily welded, and suitable for producing general purpose tools; however, it also contained many impurities, had low tensile strength, and took considerable effort to work into functional objects. Later, furnaces hot enough to melt iron were developed, allowing for the production of cast iron. The higher carbon content of cast iron made it too brittle for use in weapons or tools that would sustain impact, but it was more resistant to rust than wrought iron and could easily be cast in desired forms.

Early forms of iron working are now largely obsolete, though traditional cast iron is still used for cookware, and a related product engineered to be less brittle, ductile iron, is often used for water and sewer lines. Using iron to its full potential requires careful control of its composition, which allows for the production of alloys with a wide range of properties. Most ferrous alloys in common use are steels, meaning that they are primarily iron with a carbon composition between 0.002 and 2.1 percent, which results in a product that is neither too soft nor too brittle. Steel was produced sporadically as early as 4000 years ago, and by 500-400 BCE, cultures around the world produced the metal regularly, but the methods used were labor intensive and costly, and the metal was used only when there was no alternative--primarily for items requiring a hard, sharp edge, such as knives, razors, and swords. Methods slowly improved over the centuries, but it wasn’t until the introduction of the Bessemer process in 1855 that steel was produced cheaply and in the large quantities necessary for modern industry.

Today, literally hundreds of varieties of steels are produced for various applications. Simple carbon steel, consisting only of iron and carbon, is sufficient for many uses, from structural applications to springs and high strength wires. Addition of other elements, however, provides many advantages. Low alloy steel contains ten percent or less of elements other than iron and carbon, usually added to improve hardenability. Stainless steels contain at least eleven percent chromium, sometimes along with other elements, and are designed to resist corrosion. Many other specialty steels exist, including tool steels, which include large amounts of tungsten or cobalt and can maintain a long-lasting shape edge, and Cor-ten, a steel that weathers to a uniform rusted surface that is stable without surface treatments.

Iron is also used to produce magnets. Ferrite magnets are non-conductive magnetic ceramics made of iron oxide, and are frequently used in transformers, electromagnets, and radios. Neodymium-iron-boron magnets are the strongest permanent magnets known, and are used in motors, hard-disk drives, and magnetic fasteners. Before the development of such rare earth magnets, the strongest known magnets were alloys of iron, nickel, aluminum, and cobalt known as Alnico magnets. These are still used widely in almost any application where strong permanent magnets are needed, but increasingly neodymium magnets are used when their higher strength for a given size is a more important factor than their increased cost. Additionally, iron nanoparticles can be suspended in liquid to produce magnetic suspensions known as ferrofluids; these are used widely in ferrofluidic seals.

In addition to use in alloys and magnets, iron is commonly used in the form of compounds. Prussian blue, one of the first synthetic pigments produced, is an iron compound with a complex structure, and its brilliant color results from the presence of iron in multiple oxidation states. It is used widely in blue and black inks and paints, and produces the familiar blue of blueprints. Iron chloride is used in water treatment, as a catalyst, and to etch copper as part of the production of printed circuit boards. Iron pyrite, also known as fool’s gold, is a semiconductor that is of interest for use in photovoltaic devices, though crystal defects in the material as commonly grown have presented a challenge for researchers. Iron is also a vital trace nutrient, and is frequently used as a nutritional supplement, often in the form of iron sulfate.

Though iron silicates and carbonates are more common natural sources of the metal, all industrial sources are iron oxide ores, as the metal can be more easily extracted from these ores than more common forms. The highest quality deposits are hematite, which can be up to seventy percent irons, but some magnetite ores are also economically feasible iron sources.

Products

Iron and its compounds have numerous uses. It is the most commonly used metal for commercial applications due to its hardness, historical availability, and low cost. Once used on its own, it is now alloyed with carbon, nickel and other elements to produce steel and other high strength, non-corrosive, structural metals.  Iron is a primary colorant in glass and ceramics.

Iron is a primary colorant in glass and ceramics.  It is also used as a catalyst. It is the basis for low grade magnets and, because of its magnetic properties, is used in memory tape and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Iron is available as metal and compounds with purities from 99% to 99.999% (ACS grade to ultra-high purity). Elemental or metallic forms include pellets, rod, wire and granules for evaporation source material purposes. Iron nanoparticles and nanopowders are also available. Oxides are available in powder and dense pellet form for such uses as optical coating and thin film applications. Oxides tend to be insoluble. Iron fluorides are another insoluble form for uses in which oxygen is undesirable such as metallurgy, chemical and physical vapor deposition and in some optical coatings. Iron is also available in soluble forms including chlorides, nitrates and acetates. These compounds can be manufactured as solutions at specified stoichiometries.

It is also used as a catalyst. It is the basis for low grade magnets and, because of its magnetic properties, is used in memory tape and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Iron is available as metal and compounds with purities from 99% to 99.999% (ACS grade to ultra-high purity). Elemental or metallic forms include pellets, rod, wire and granules for evaporation source material purposes. Iron nanoparticles and nanopowders are also available. Oxides are available in powder and dense pellet form for such uses as optical coating and thin film applications. Oxides tend to be insoluble. Iron fluorides are another insoluble form for uses in which oxygen is undesirable such as metallurgy, chemical and physical vapor deposition and in some optical coatings. Iron is also available in soluble forms including chlorides, nitrates and acetates. These compounds can be manufactured as solutions at specified stoichiometries.

Iron Properties

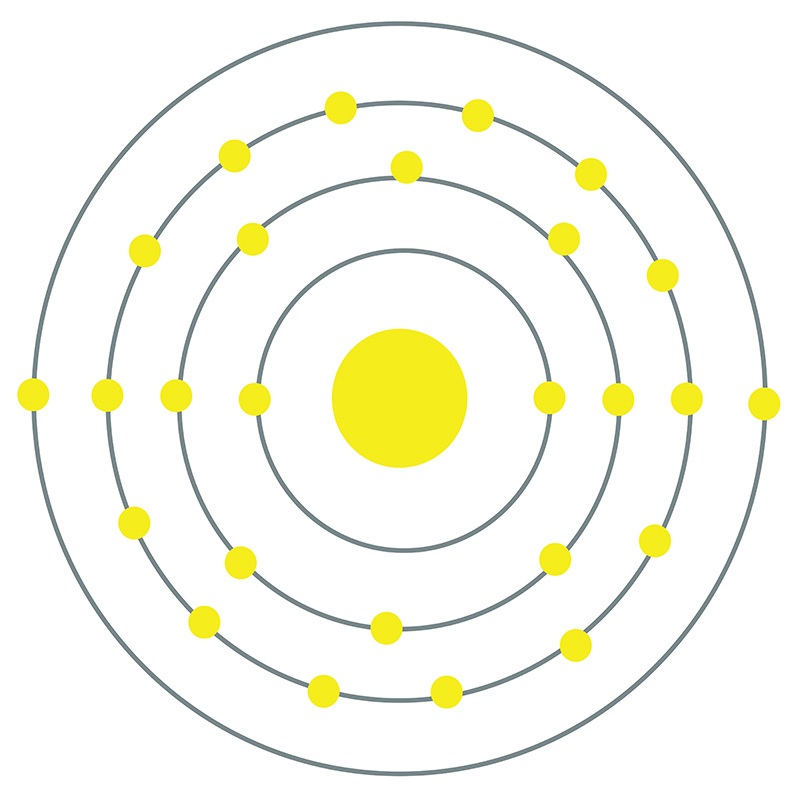

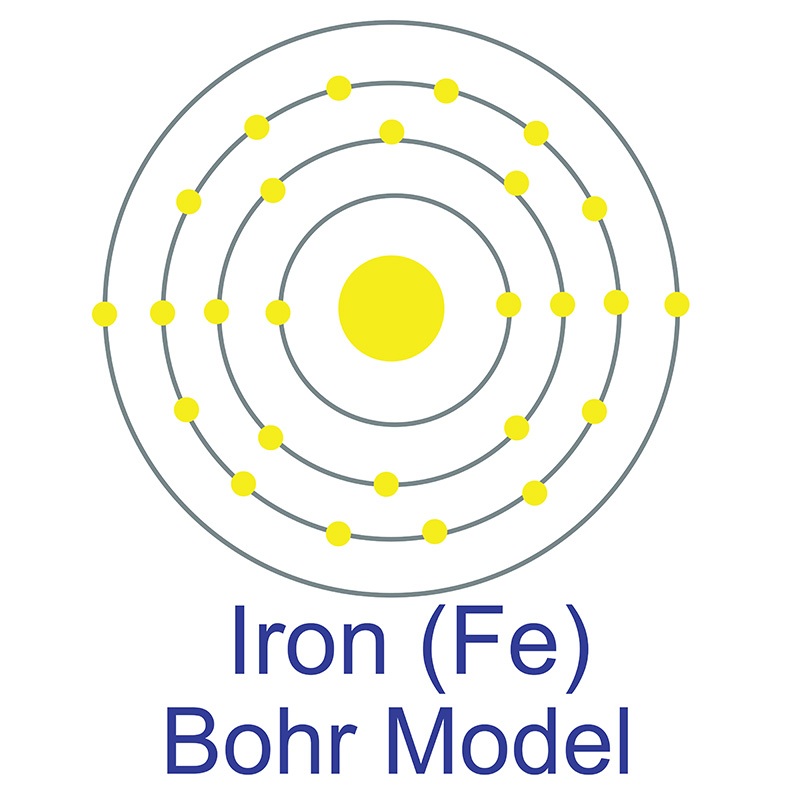

Iron is a Block D, Group 8, Period 4 element. The number of electrons in each of Iron's shells is 2, 8, 14, 2 and its electron configuration is [Ar] 3d6 4s2.

Iron is a Block D, Group 8, Period 4 element. The number of electrons in each of Iron's shells is 2, 8, 14, 2 and its electron configuration is [Ar] 3d6 4s2.  The iron atom has a radius of 124.1.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 200.pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7439-89-6, Iron has a lustrous grayish metallic appearance. Iron is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust and the most common element by mass forming the planet earth as a whole. Iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (Fe2O3), goethite (FeO(OH)), limonite (FeO(OH) . n(H2O)) or siderite (FeCO3). It is rarely found in its pure metallic form since it tends to oxidize.

The iron atom has a radius of 124.1.pm and its Van der Waals radius is 200.pm. In its elemental form, CAS 7439-89-6, Iron has a lustrous grayish metallic appearance. Iron is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust and the most common element by mass forming the planet earth as a whole. Iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (Fe2O3), goethite (FeO(OH)), limonite (FeO(OH) . n(H2O)) or siderite (FeCO3). It is rarely found in its pure metallic form since it tends to oxidize.

Health, Safety & Transportation Information for Iron

Iron is not toxic; however, safety data for Iron and its compounds can vary widely depending on the form. For potential hazard information, toxicity, and road, sea and air transportation limitations, such as DOT Hazard Class, DOT Number, EU Number, NFPA Health rating and RTECS Class, please see the specific material or compound referenced in the Products tab. The below information applies to elemental (metallic) Iron.

| Safety Data | |

|---|---|

| Signal Word | N/A |

| Hazard Statements | N/A |

| Hazard Codes | N/A |

| Risk Codes | N/A |

| Safety Precautions | N/A |

| RTECS Number | N/A |

| Transport Information | N/A |

| WGK Germany | nwg |

| Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling (GHS) |

N/A |

Iron Isotopes

Iron has 4 stable isotopes: 54Fe (5.845%), 56Fe (91.754%)57, Fe (2.119%) and 58Fe (0.282%).

| Nuclide | Isotopic Mass | Half-Life | Mode of Decay | Nuclear Spin | Magnetic Moment | Binding Energy (MeV) | Natural Abundance (% by atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45Fe | 45.01458(24)# | 4.9(15) ms [3.8(+20-8) ms] | ß+ to 45Mn; ß+ + 2p to 43Mn | 3/2+# | N/A | 321.33 | - |

| 46Fe | 46.00081(38)# | 9(4) ms [12(+4-3) ms] | ß+ to 46Mn; ß+ + p to 45Mn | 0+ | N/A | 342.45 | - |

| 47Fe | 46.99289(28)# | 21.8(7) ms | ß+ to 47Mn; ß+ + p to 46Mn | 7/2-# | N/A | 357.98 | - |

| 48Fe | 47.98050(8)# | 44(7) ms | ß+ to 48Mn; ß+ + p to 47Mn | 0+ | N/A | 377.24 | - |

| 49Fe | 48.97361(16)# | 70(3) ms | ß+ + p to 48Mn; ß+ to 49Mn | (7/2-) | N/A | 391.84 | - |

| 50Fe | 49.96299(6) | 155(11) ms | ß+ to 50Mn; ß+ + p to 49Mn | 0+ | N/A | 410.16 | - |

| 51Fe | 50.956820(16) | 305(5) ms | ß+ to 51Mn | 5/2- | N/A | 423.83 | - |

| 52Fe | 51.948114(7) | 8.275(8) h | EC to 52Mn | 0+ | N/A | 439.36 | - |

| 53Fe | 52.9453079(19) | 8.51(2) min | EC to 53Mn | 7/2- | N/A | 450.24 | - |

| 54Fe | 53.9396105(7) | STABLE | - | 0+ | N/A | 463.91 | 5.845 |

| 55Fe | 54.9382934(7) | 2.737(11) y | EC to 55Mn | 3/2- | N/A | 472.92 | - |

| 56Fe | 55.9349375(7) | STABLE | - | 0+ | N/A | 484.72 | 91.754 |

| 57Fe | 56.9353940(7) | STABLE | - | 1/2- | 0.09062294 | 491.87 | 2.119 |

| 58Fe | 57.9332756(8) | STABLE | - | 0+ | N/A | 501.81 | 0.282 |

| 59Fe | 58.9348755(8) | 44.495(9) d | ß- to 59Co | 3/2- | 0.29 | 508.96 | - |

| 60Fe | 59.934072(4) | 1.5(3)E+6 y | ß- to 60Co | 0+ | N/A | 517.04 | - |

| 61Fe | 60.936745(21) | 5.98(6) min | ß- to 61Co | 3/2-,5/2- | N/A | 523.25 | - |

| 62Fe | 61.936767(16) | 68(2) s | ß- to 62Co | 0+ | N/A | 531.33 | - |

| 63Fe | 62.94037(18) | 6.1(6) s | ß- to 63Co | (5/2)- | N/A | 535.68 | - |

| 64Fe | 63.9412(3) | 2.0(2) s | ß- to 64Co | 0+ | N/A | 542.83 | - |

| 65Fe | 64.94538(26) | 1.3(3) s | ß- to 65Co | 1/2-# | N/A | 547.18 | - |

| 66Fe | 65.94678(32) | 440(40) ms | ß- to 66Co; ß- + n to 65Co | 0+ | N/A | 554.33 | - |

| 67Fe | 66.95095(45) | 394(9) ms | ß- to 67Co; ß- + n to 66Co | 1/2-# | N/A | 558.68 | - |

| 68Fe | 67.95370(75) | 187(6) ms | ß- to 68Co; ß- + n to 67Co | 0+ | N/A | 563.97 | - |

| 69Fe | 68.95878(54)# | 109(9) ms | ß- to 69Co; ß- + n to 68Co | 1/2-# | N/A | 567.39 | - |

| 70Fe | 69.96146(64)# | 94(17) ms | Unknown | 0+ | N/A | 572.67 | - |

| 71Fe | 70.96672(86)# | 30# ms [>300 ns] | Unknown | 7/2+# | N/A | 576.09 | - |

| 72Fe | 71.96962(86)# | 10# ms [>300 ns] | Unknown | 0+ | N/A | 581.37 | - |